If you’ve found yourself wondering how these times of increased stress, anxiety, and uncertainty will affect your children’s mental health, you’re far from alone.

As the tensions mount and the pandemic isolation continues, you can’t help questioning not just how long the pandemic will last, but how lasting and traumatic the effects will be for children coming of age in this environment. Masks. Fear of germs. Fear of touching other people. In an ideal world, these are not the lessons we wanted to be teaching, or our children having to learn.

Let’s keep three things in mind:

From birth, the brain is developing rapidly – so rapidly that 90 percent has developed before our kids go off to kindergarten (regardless of whether they physically go to kindergarten). Brain functioning is the interaction between genetics, and experience. It is particularly sensitive to environmental influences, and yes, daily experiences and stresses can impact the developing brain’s malleable architecture. That’s why parents, caregivers, and educators are such important gatekeepers: They play an important role in not only the type of experiences children are exposed to, but how they make sense of them.

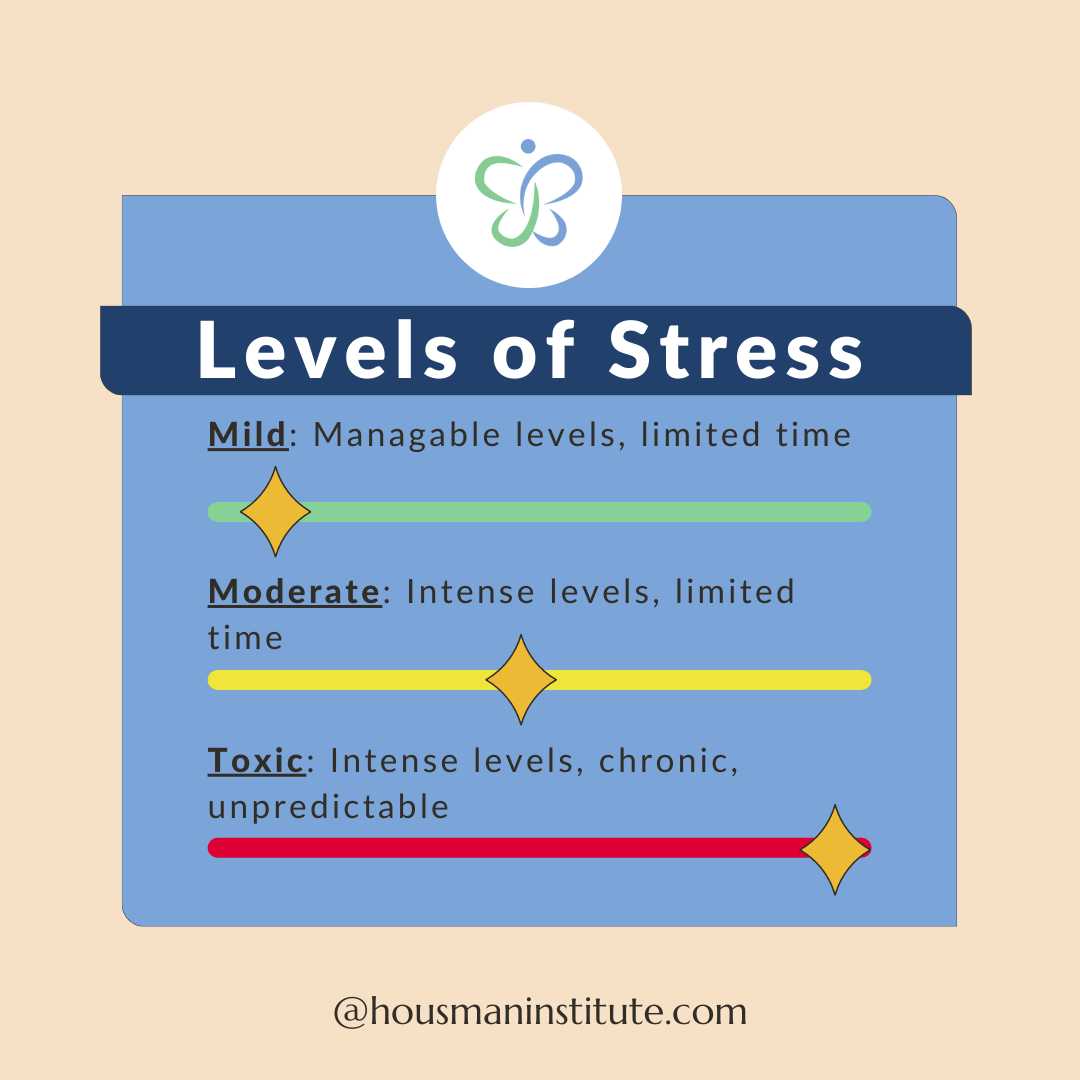

When thinking about the anxiety of daily life amid a pandemic, it can be helpful to think from the perspective of degree. There are different degrees of stress, ranging from mild to toxic.

All of us experience the range of mild to tolerable times of stress and anxiety at some points in our lives. The good news is, there are ways to effectively cope with and mange these stresses, coming away stronger and with our wits about us. The important thing to keep in mind is that the major difference between children coming away vulnerable or resilient has to do in large part with nurturing relationships—caregivers responsive to children’s cues, gestures, behaviors, and emotions. The developing brain recovers and continues to thrive with responsive and supportive relationships, reducing tension while stimulating healthy neural circuits and pathways that learn to deal effectively with the strain.

This is what it’s not: Being a superhero that can do it all, 24/7, and it’s not ignoring your own heightened, gnawing stress. Being responsive means being aware of your child’s emotions, but also being aware of and allowing for your own emotions so that you can be available to those of your child. Emotion is our children’s first language and they are great emotional detectives, sensing when we may be feeling angry or afraid, then feeding off our emotions and responding in kind. When we give ourselves permission to acknowledge that our emotions are real and accept that they can be dealt with, the intensity of our feelings dissipate much more quickly. Then we’re better able to perceive and hear our children’s feelings and help them deal with their emotions, promoting their sense of confidence, empowerment, and control.

Children naturally express their emotions in action rather than words. But key adults can help rechannel and translate their behavior into words by helping them identify, constructively express, and effectively regulate their emotions. As caring adults, we’re better able to appreciate the root of the behavior before responding to the action. In that way, we guide them toward putting words to their emotions, engaging and encouraging them to address the concern. This increases their feeling of control, while decreasing their tension and stress—as well as yours.

Amid the disruption like the one they’ve been thrust into with the pandemic, it’s helpful to remind children of the things that remain the same. Mealtime routines, bedtime rituals, and bath-time games are all essential when so much of what they knew to be familiar has changed, and feels beyond their control.

Being responsive and engaging with children is the best emotional security blanket to envelop them during the ongoing uncertainty we’re all facing. This, more than anything, keeps moderate stress from becoming toxic. You are best able to provide that blanketing when your own mind and body are well cared for. If your needs aren’t being met, it’s hard if not impossible to muster the energy to be available to your child.

Remember that there is not one size that fits all in dealing with difficult circumstances, and as we said, children are resilient. A parent’s positive attitude and support go a long way toward overriding the negative perception of difficult situations. However, there are times when a family might have experienced a more severe trauma or hardship — physical danger, substance abuse, chronic housing or food insecurity — and working with a specialist is not only helpful, but necessary. We are only human, and we only have so many tools in the box.

Dealing with trauma head-on takes strength, and courage. There’s no shame in getting help from someone with a more specialized toolbox.

These Posts on Anxiety

Housman Institute, LLC

831 Beacon Street, Suite 407

Newton, MA 02459

info@housmaninstitute.org

(508)379-3012

Explore

Our Products

Legal

Connect

Contact

Join our Mailing List!

Subscribe to receive our newsletter, latest blogs, and SEL resources.

We respect and value your privacy.

No Comments Yet

Let us know what you think