Read more to learn what is Emotional Intelligence, what are the four quadrants of Emotional Intelligence, and some language tips for fostering Emotional Intelligence integrated with a real-life parent scenario.

As an educator and parent, I have learned just how much children listen to our conversations and imitate our interactions and reactions.

After months of expressing gratitude in front of my children, I felt overjoyed when my three-year-old started saying, “That was really nice of them, right Mom? That made me so happy!”

After hearing her say that the first time, I realized that she was copying moments of gratitude that I purposely express in front of my children.

Something as simple as saying how grateful I am in front of my children has taught them the importance of using their words to talk about their emotions and feelings.

During my time as a teacher, similar situations would occur every day. Children would come into the classroom and tell vivid stories about their weekends and situations with their families.

I remember one moment in particular with a 4-year-old (we’ll call her Jasmine) in my class. She began re-enacting a fight between her parents while she was playing in the dramatic play area with a friend.

My co-teacher and I quickly got involved because the child had obviously witnessed a situation that she shouldn’t have. We sat Jasmine down in the cozy corner and allowed her space to discuss her feelings about the situation.

These types of difficult situations can happen to anyone. We are all human, and we all make mistakes. As educators, we can learn the tools, language, and techniques to respond to children when they share difficult moments like this with us and help support parents in doing the same at home.

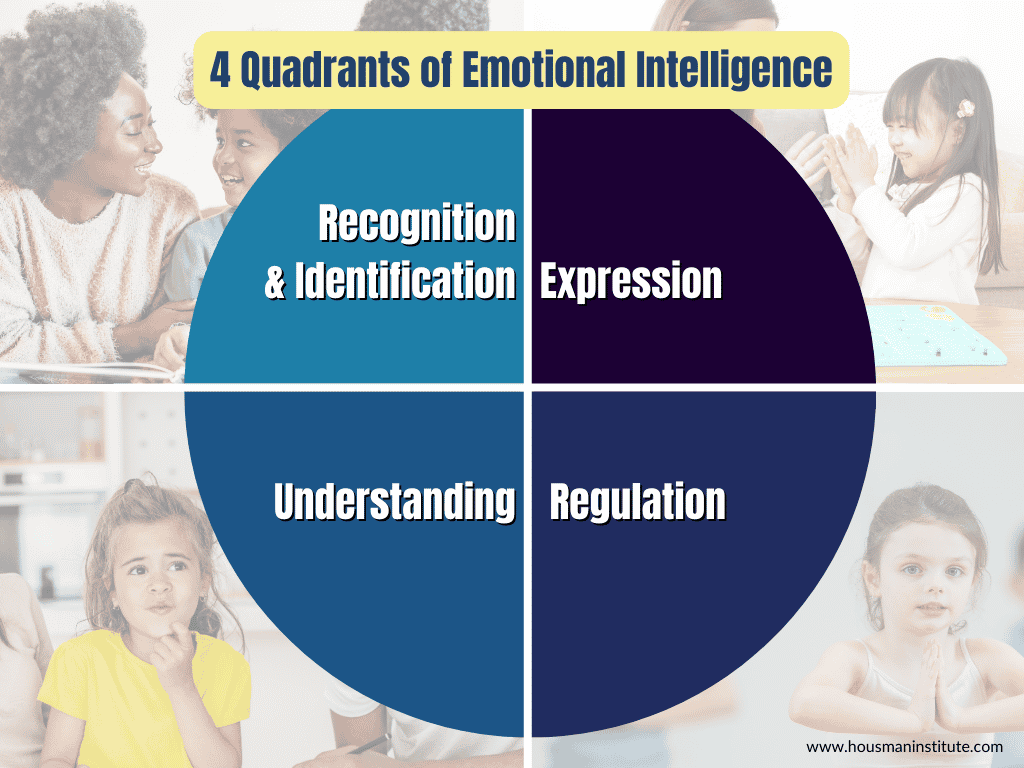

Children experience big emotions daily and need supportive caregivers to help them develop the four quadrants of emotional intelligence to better manage and regulate emotions effectively, work with peers, and empathize with others.

Emotional Intelligence is the ability to recognize, understand, express, and regulate our own emotions and those of others. Having these skills enables children and adults to be self-aware, more empathetic towards others, and better able to problem-solve.

Parents and caregivers can promote the four quadrants of emotional intelligence by using Emotional Learning (EL) language in the classroom and at home.

This may seem like a lot, but you may be promoting these quadrants and skills in your everyday conversations without even realizing it — take it from me!

Recently, my five-year-old son had to have surgery. I decided that rather than springing it on him, I would have conversations with him about the upcoming event to ease his anxiety.

After days of tears and worry, even with our calm talks, the day of the surgery arrived, and it was apparent that he wasn’t feeling confident about the situation. When I tried to help him out of the car, he unbuckled and jumped to the front seat, crying and begging us to cancel the surgery.

After several minutes of answering his questions calmly, he finally came around and allowed me to help him out of the car. As we started to walk inside, he tried to take off in full sprint through the parking lot. It was obvious that he was overwhelmed and anxious. Once we got inside, we were quickly escorted back to the pre-op area, and the tears were flowing.

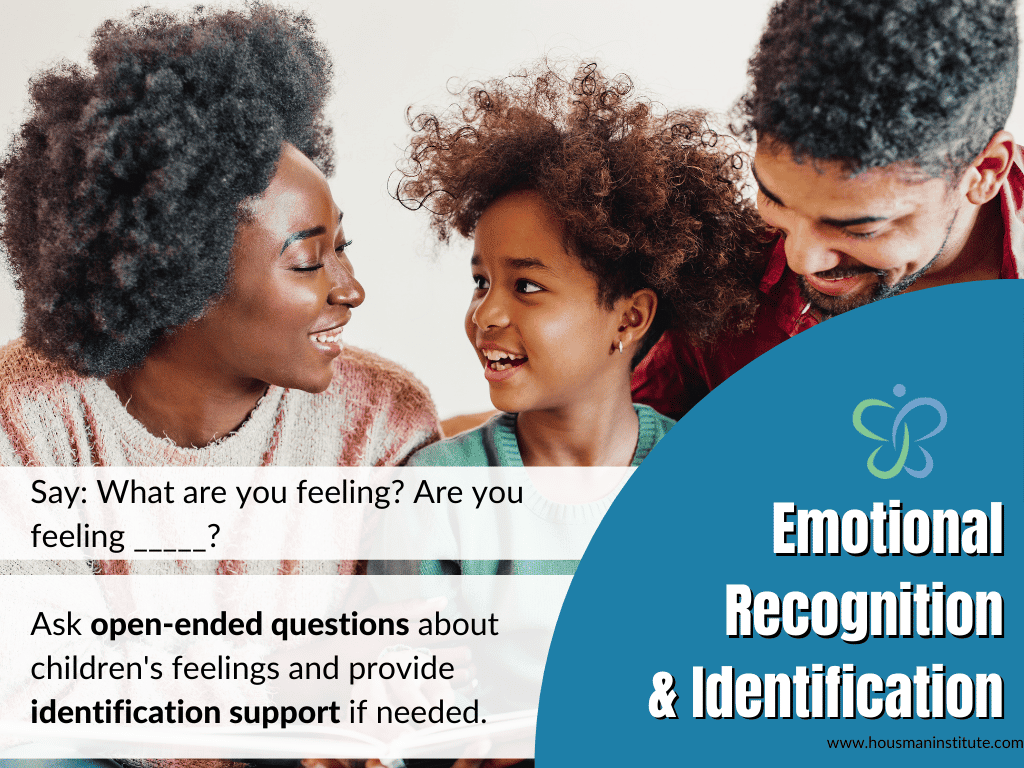

Although he was upset, it was important to me that he understood that feeling nervous, sad, or scared was okay. I started a calm conversation with him about what I was noticing: “You seem a little quiet. Are you feeling nervous about today? Can you tell me what you’re feeling?”

Using language like this example can help children identify and recognize what they are feeling, which is the first quadrant of emotional intelligence.

He quickly replied, “I don’t want to do this! I am very scared of the IV!” I knew this was his biggest fear, so I kept the conversation going to help him talk through what was happening in his body when he felt these intense emotions and how we could work together to solve the problem.

Next, I reassured him that he wouldn’t be awake for this part, but he instantly told me he was still “VERY scared!”

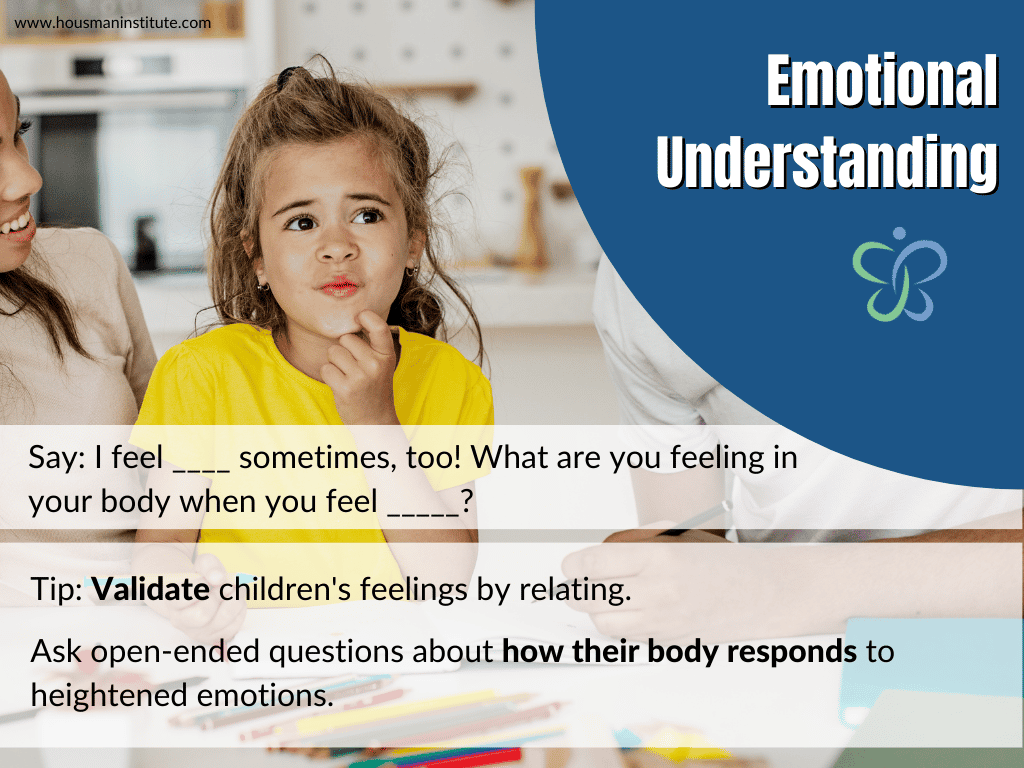

I said, “I feel scared sometimes, too! When I feel scared, my hands can get sweaty, and I feel a little shaky and nervous. What are you feeling in your body when you feel scared?”

He replied, “I feel sick to my stomach and very, VERY nervous!”

This is an example of emotional understanding.

My son was able to explain not only why he was nervous but also how his body reacted to the intense emotions. I wanted to make sure he didn’t feel alone, so I tried my best to relate to him by letting him know that I have similar emotions from time to time.

Supporting children in connecting their emotions to their bodily responses can help them become more self-aware and better prepared to handle the emotion the next time.

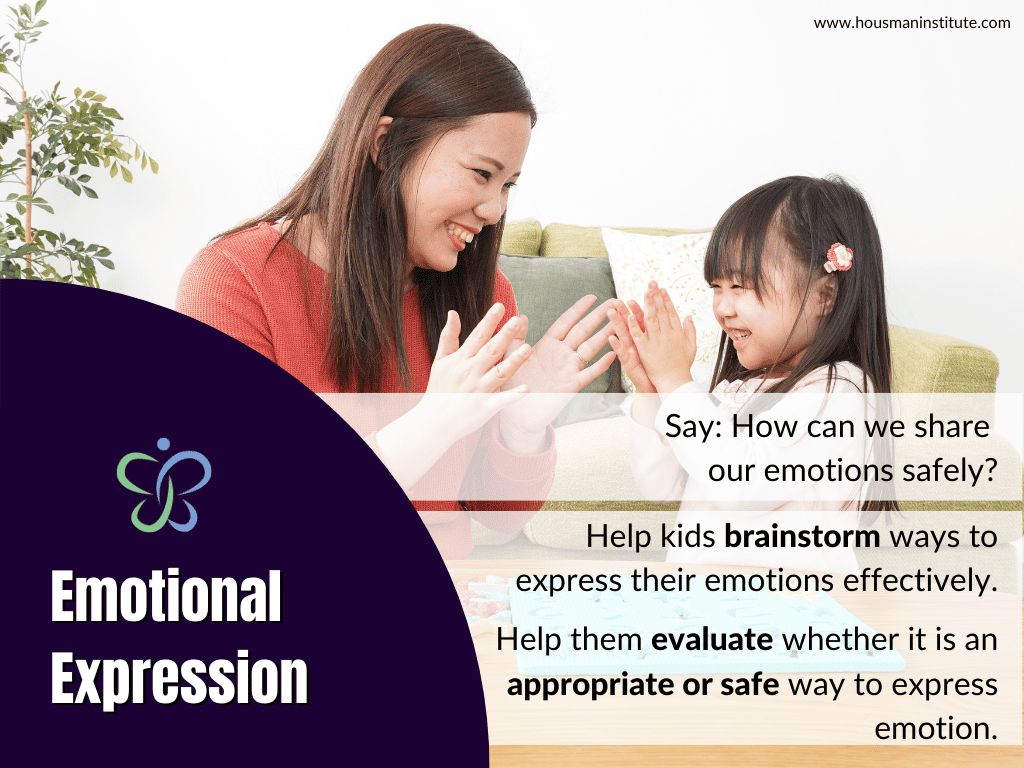

I continued with the conversation by discussing ways to express our emotions. I asked, “When you’re feeling scared, is it best to run away from Mommy and Daddy?”

He said, “No, Mommy! I just really didn’t want to come inside.”

I replied, “I know you didn’t, buddy, but that could be unsafe, especially when we are in a parking lot. What else could you do to let Mommy know you are feeling scared?”

He thought for a moment and responded, “I could ask you to hold me and whisper that I am feeling scared in your ear.”

I said, “That’s a great way to tell me that you’re feeling scared!”

This language example is one way we can promote constructive emotional expression.

Sometimes during difficult situations and intense emotions, children need extra support in learning ways to express their emotions appropriately and safely, as you can see from this part of the conversation. Caregivers can foster effective emotional expression by modeling, guiding, and discussing various ways to express emotions.

You can also share your ideas and provide options when needed.

Luckily, I knew he wouldn’t be awake for the IV, so I was able to calm his mind about the rest of the morning by talking him through each step of the process.

After explaining each step, I asked if there was anything that would help him feel better.

He mentioned deep breaths because it is a technique we use daily at home.

I modeled our routine for the first few moments until he felt comfortable joining in. I said, “Let’s practice taking a deep breath like we are smelling a flower. Now, let’s pretend we are blowing out a big birthday candle! Ready?”

He joined me, and we practiced our deep breathing several times. By the time the doctor came in to talk to us, my son was emotionally regulated and could even talk to the doctor without tears.

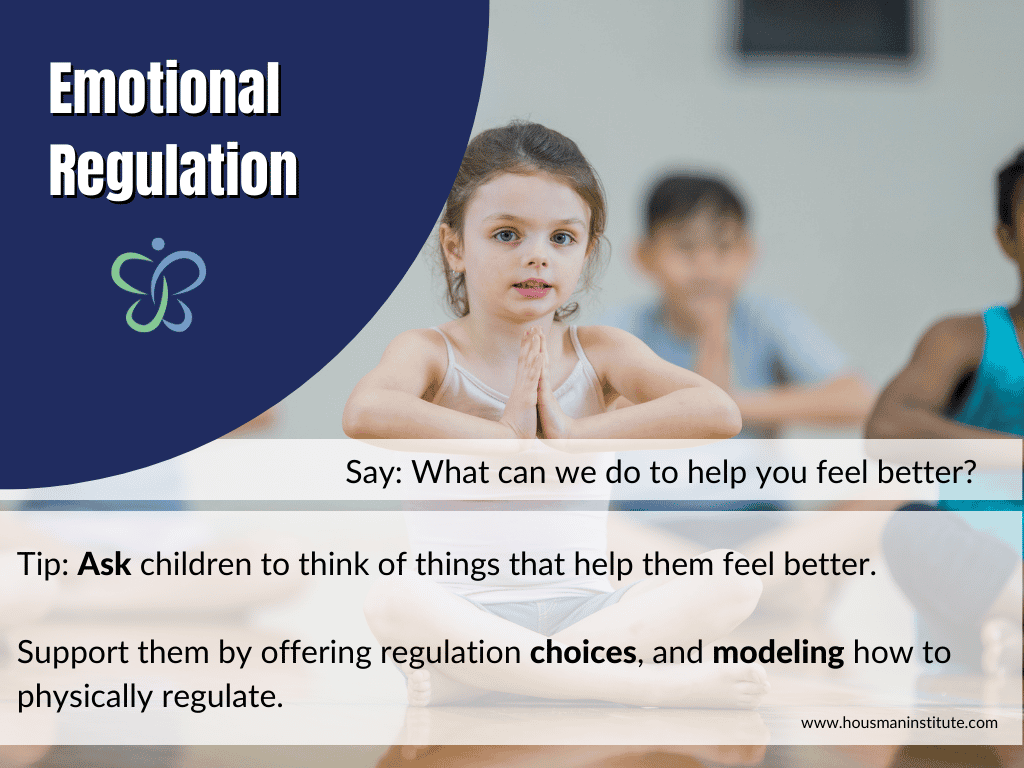

This language is an example of emotional regulation. In the heat of the moment, children may not be able to calm down on their own or know what to do. We can support their regulation skills by asking what can help them feel better or offering feel-better choices. Sometimes, even something as simple as a hug can help children regulate their emotions.

Believe it or not, my son let the anesthesiologist carry him back to the operating room when it was time for surgery. His ability to regulate his emotions allowed him to calm himself down enough to know that he was loved, safe, and cared for and that everyone there only wanted to help him.

Related: The Ultimate Guide for Talking to Kids About Tough Topics

Taking a few moments to have these conversations with my son encouraged him to recognize and identify the emotions that he was experiencing, understand his emotions and what was causing them, express his emotions safely and constructively, and practice regulation techniques in the heat of the moment.

Whenever you anticipate a child may be experiencing heightened emotions, you can talk them through the process to help them to calm down or remain calm.

These conversations will come naturally with practice. Next time a child in your care is experiencing heightened emotions, practice supporting them by talking through the problem while considering the four quadrants of emotional intelligence.

Housman Institute, LLC

831 Beacon Street, Suite 407

Newton, MA 02459

info@housmaninstitute.org

(508)379-3012

Explore

Our Products

Legal

Connect

Contact

Join our Mailing List!

Subscribe to receive our newsletter, latest blogs, and ECSEL resources.

We respect and value your privacy.

Comments (1)